The past week has been tough on my 6 year old son: difficulty with the kid across the street, whom he considers his best friend. Feelings have been hurt in both directions and neither boy is handling it well. Thus far, they have each perpetuated the cycle of my-feelings-are-hurt-so-I’m-going-to-hurt-your-feelings.

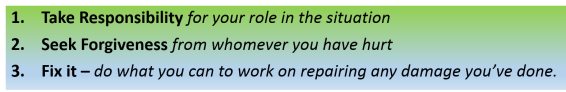

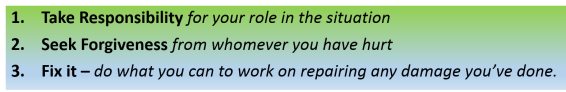

When our kids make mistakes, we teach them:

Forgiveness is hard, and it’s hard for different people for different reasons. Everyone has that one aspect that they struggle with, whether it’s forgiving oneself, forgiving others, or seeking forgiveness.

Forgiveness is hard, and it’s hard for different people for different reasons. Everyone has that one aspect that they struggle with, whether it’s forgiving oneself, forgiving others, or seeking forgiveness.

So when discussing why the cycle of my-feelings-are-hurt-so-I’m-going-to-hurt-your-feelings was wrong (and unhelpful, and hurtful), it didn’t surprise me when my son started crying. But instead of assuming, I compassionately asked “Why are you crying?”

“Because I know what I did was wrong and I’m ashamed.”

Oh honey. No. That’s not what I want. That’s not what God wants.

Forgiveness of Self

Shame breaks forgiveness. It stops us from learning, growing, healing, and loving. Shame paralyzes us in Part 1: Take Responsibility, and it brings its friend Fear to prevent us from Part 2: Seeking Forgiveness from whoever you’ve hurt… so that we might as well forget about making any progress on Part 3: Fixing It. That paralysis not helpful.

For many of us, the hardest part about forgiveness is honestly forgiving ourselves.

How could I have been so stupid? How could I have made such an awful mistake?

Some wonder: can we forgive ourselves? Isn’t it up to God to forgive us? To that I’d respond: certainly. God is ultimately the one who forgives. But Jesus offered extra clarification here: we’re not supposed to be judging and condemning ourselves in the first place.

Read the story of the woman caught in the act of adultery:

“Teacher, this woman was caught in the very act of committing adultery. Now in the law, Moses commanded us to stone such women. Now what do you say?” They said this to test him, so that they might have some charge to bring against him. Jesus bent down and wrote with his finger on the ground. When they kept on questioning him, he straightened up and said to them, “Let anyone among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her.” And once again he bent down and wrote on the ground. When they heard it, they went away, one by one, beginning with the elders; and Jesus was left alone with the woman standing before him. Jesus straightened up and said to her, “Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?” She said, “No one, sir.” And Jesus said, “Neither do I condemn you. Go your way, and from now on do not sin again.” (John 8:4-11)

Look closely at the final words Jesus said to the woman, “Neither do I condemn you. Go your way, and from now on do not sin again.”

God is a God of love and life. Shame and condemnation are not what God wants for our lives. Rather, Jesus tells us to learn and grow from this experience (sin no more) and go on your way–move forward in life with love.

Forgiveness of Others

Jesus speaks most clearly on the topic of forgiving others, particularly telling us to love our enemies (Matthew 5:44, Luke 6:27) and forgive seven times seven times (Matthew 18:21-22, Luke 17:4). Taken as a whole, Jesus’ message of forgiveness is radical:

We are to be people of love and reconciliation, not people of hate and vengeance.

There is no wiggle room in Christianity when it comes to hatred and vengeance. Most Christians agree with this in theory, but have difficulty when putting it in to practice. Especially in instances of abuse. Particularly when it comes to the teaching about retaliation.

You have heard that it was said, “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.” But I say to you, Do not resist an evildoer. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other also. (Matthew 5:38-39)

At no point in the Gospels does Jesus preach a message contrary to love. Abuse is not love. So to interpret this passage in a way that encourages someone to endure ongoing, continued abuse would be a gross misinterpretation. Still, what is Jesus saying here? Protestant biblical scholar, Walter Wink (d. 2012) offers an interesting exegesis of this passage in The Powers That Be (1998).

Contemporary readers usually imagine these “strikes” as a fist fight. Actually, in biblical times it was common for a “Master” (Roman/male) to backhand-slap an inferior (slaves, wives, children, Jews). Jesus is speaking to people who are used to being degraded, telling them to refuse to accept that kind of treatment any more. However, Jesus does not encourage them to retaliate and respond with violence. Instead, he instructs them to be subversive with creative non-violence. By literally, physically turning and offering “the other cheek” to the oppressor, the “master” can no longer backhand-slap; the only possible “hit” would be with a fist to the left cheek. In that society, only equals fought with fists; thus “turning the other cheek” was an act of defiance that honored human dignity. (Click here for the full explanation.)

Using love and respect for human dignity to guide forgiveness, let us also explore what it means to forgive a person who is unrepentant.

As a child, Grace was molested by an uncle who lived with her large Catholic family for years, but she never told anyone. As an adult, when Grace tells her story, she recognizes that though it remained a secret, there were signs of extreme self-loathing that permeated her childhood and adolescence, lasting into much of her adulthood. Grace’s uncle had long since passed away, never acknowledging or apologizing for his actions. She knew that she needed forgiveness and healing in this area of her life. However, when Grace talked about forgiveness, she focused on her need to forgive her molester. “I struggle with that, because it seems like saying that I’m okay with what he did. And I’m not.”

When Jesus spoke to his disciples about forgiveness, he was calling them to reconcile, love, and be at peace with one another. While “reconciliation” is only possible between two people who come together in mutual respect, forgiveness itself isn’t dependent on anyone else’s actions or words.

PBS did a segment on “Understanding Forgiveness” in a series called “This Emotional Life,” in which psychologist Sonja Lyubomirsky calls forgiveness “a shift in thinking” toward someone who has wronged you, “such that your desire to harm that person has decreased and your desire to do him good (or to benefit your relationship) has increased.” Forgiveness, at a minimum, is a decision to let go of the desire for revenge and ill-will toward the person who wronged you.

- Forgiveness is not the same as reconciliation. Forgiveness is one person’s inner response to another’s perceived injustice. Reconciliation requires both parties working together. Forgiveness is something that is entirely up to you.

- Forgiveness is not forgetting. “Forgive and forget” seem to go together. However, the process of forgiving involves acknowledging to yourself the wrong that was done to you, reflecting on it, and deciding how you want to think about it. Focusing on forgetting a wrong might lead to denying or suppressing feelings about it, which is not the same as forgiveness. Forgiveness has taken place when you can remember the wrong that was done without feeling resentment or a desire to pursue revenge. Sometimes, after we get to this point, we may forget about some of the wrongs people have done to us. But we don’t have to forget in order to forgive.

- Forgiveness is not condoning or excusing. Forgiveness does not minimize, justify, or excuse the wrong that was done. Forgiveness also does not mean denying the harm and the feelings that the injustice produced. And forgiveness does not mean putting yourself in a position to be harmed again. You can forgive someone and still take healthy steps to protect yourself, including choosing not to reconcile.*

Forgiveness is about letting go of the anger, hatred, and desire for revenge.

Grace realized that she did not hold on to hatred, anger, or a desire for revenge for her uncle. She did, however, hold on to anger and hatred for herself. When she released the idea that she was expected to “be okay” with the molestation, Grace began to heal.

Seeking Forgiveness

Sometimes we have a hard time with actually seeking forgiveness. Doing so requires vulnerability.

- Am I too proud or angry to take responsibility for my role?

- Will my apology be received?

- Will I be made to feel worse than I already do? (Is that even possible?)

- What will they think of me?

- Does apologizing make me look weak?

Jesus told us to make peace with one another before coming to the altar (Matthew 5:23-25). This peace is a matter of love and wholeness. We are told to reconcile with one another, and we are also invited to receive the healing grace in the Sacrament of Reconciliation. And what a gift of grace it is! The peace!

So while yes, it is scary to be vulnerable, Christian discipleship is about being real, taking that risk, and living in love with one another.

Reflect: When it comes to forgiveness, what aspect do you struggle with? What has been your most significant experience with forgiveness? Is there someone you need to forgive?